Released in 2011, the DQP was updated in 2014, and now in 2021, based on feedback from over 800 institutions. NILOA was delighted to oversee the revision process which included a series of working groups who provide guidance and suggestions for revising the DQP, blogs from the original DQP authors, and a public comment process to the field at large. Read the revised Birth and Growth DQP 3.0 document for a quick history of the DQP and more information that informed the revision process. A one-pager highlighting the revisions is found here.

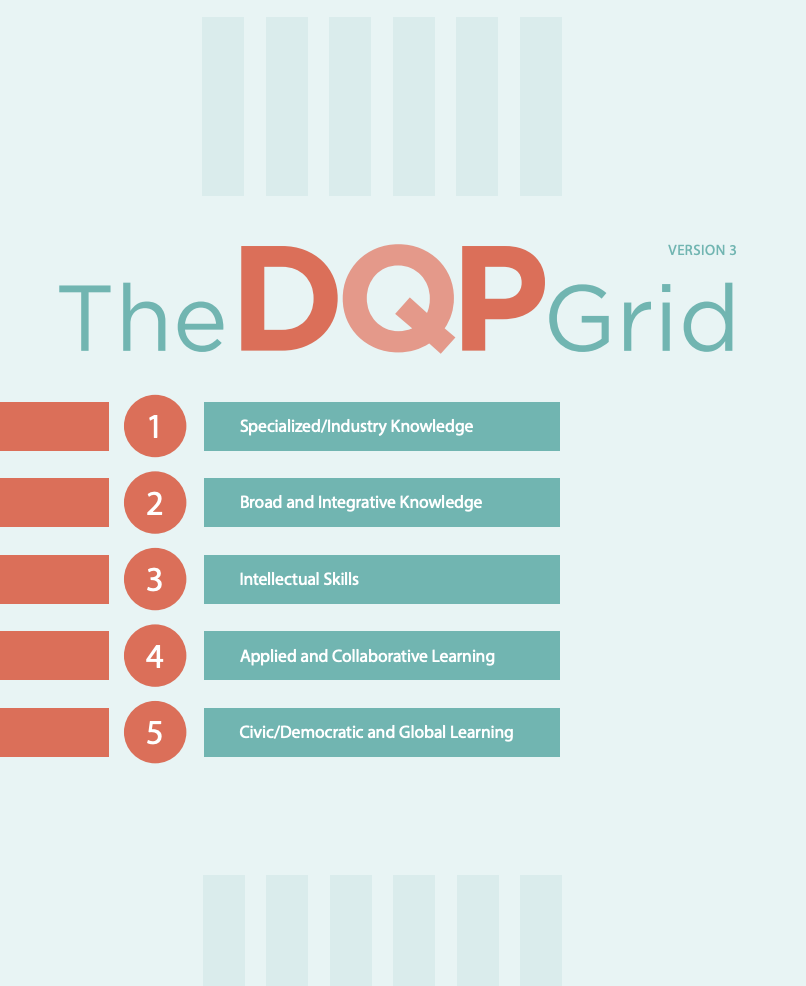

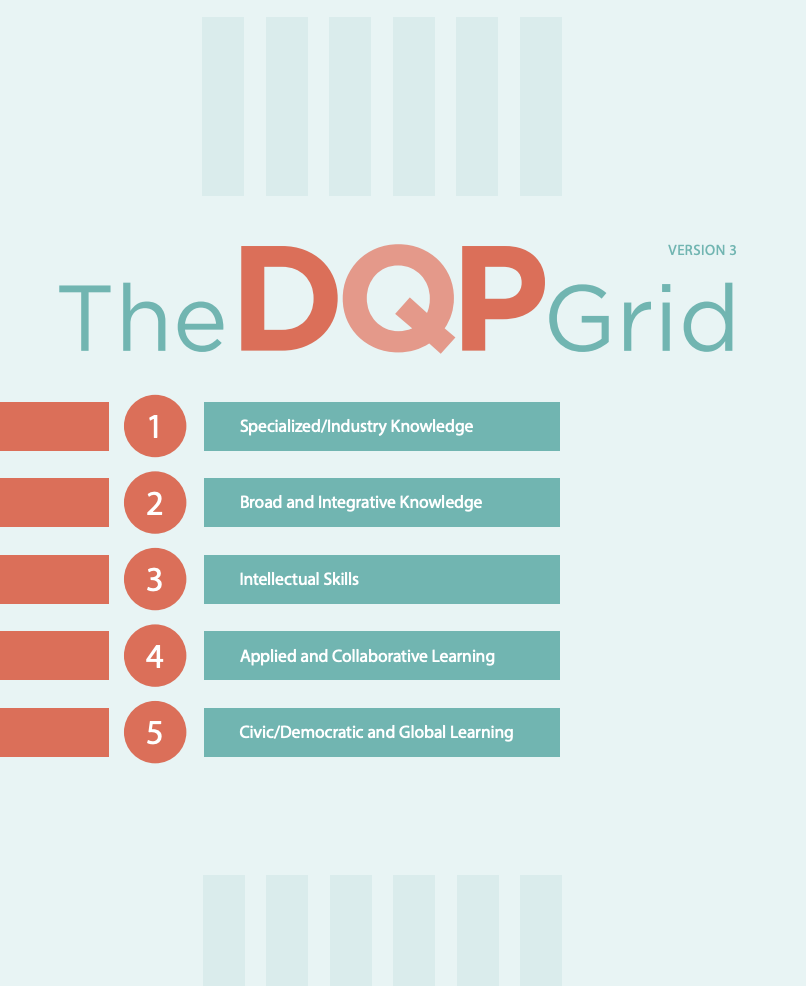

Specialized/Industry Knowledge addresses what students in any specialization, major field of study, or career pathway should demonstrate with respect to that specialization.

Broad and Integrative Knowledge asks students to bring together learning from industry knowledge, experience, and/or different fields of study to discover and explore the implications of concepts and questions that bridge essential areas of learning/practice as well as integrate their knowledge to advance solutions in support of a humane, just, and democratic society

Intellectual Skills includes: analytic inquiry, use of information resources, engaging diverse perspectives, ethical reasoning, quantitative fluency and communicative fluency.

Applied and Collaborative Learning emphasizes what students can do with what they know. Students are asked to demonstrate their learning by addressing unscripted problems in scholarly inquiry, at work and in other settings outside the classroom, individually and in teams.

Civic/Democratic and Global Learning recognizes higher education’s responsibilities both to democracy and the global community. Students engage in integration of their knowledge and skills by addressing and responding to civic, social, environmental, economic, equity, inclusion, and social justice challenges at local, national, and global levels.

Read NILOA’s 2022 report reviewing existing Institution-Level Learning Outcomes (ILOs) in relation to the DQP here.

DQP 3.0 Corner

Join us for the next few months where the co-authors of the DQP write their thoughts and considerations as we look to revise the DQP. In their respective blogs, they answer the following questions: (a) Are there ways in which the DQP might (should?) be updated to make it more relevant to the present?; (b) Should the DQP be reconfigured or reformatted to make it more appealing and accessible? Are there elements of the DQP that might be retired? Others that should be added?; and (c) Based on your experience, what advice would you have regarding the roll-out of the next iteration?

Blog No. 1 (June 2021)

THE DQP AND THE EMPHASIS ON EMPLOYABILITY

Paul L. Gaston

Consultant to Lumina Foundation

The current edition of the Degree Qualifications Profile, released by Lumina Foundation in 2014, recognizes that effective degree programs must prepare graduates for employment. Indeed, the DQP is meant to “respond directly to employers’ concerns that graduates need better preparation for applying their learning to a wide array of problems and settings” (p. 50). In announcing the 2015 edition, Jamie Merisotis, president of Lumina, spoke of the importance of the path “from a degree to a career” (p. 2). Throughout, the DQP focuses on “sound preparedness for college, career, and life” (p. 9).

How might the next iteration of the DQP draw more attention to career preparedness as an essential degree-level objective? There are opportunities to do so in every one of its elements. It will be the work of the NILOA review panels to consider revisions, but as one of the DQP authors I can suggest a few possibilities. (Two other authors of the DQP, Carol Geary Schneider and Peter Ewell, will publish their respective blogs on other issues in the July and August issues of the newsletter.)

- The summary of DQP “uses” (p. 8) could mention its value for aligning program requirements with employer expectations. Shortly after the release of the first (“beta”) edition of the DQP, the North Dakota State College of Science used it “to determine how well [its] AAS degree aligned with employer expectations.” As part of the process, “major employers of students were invited to . . . review the DQP and provide feedback” (p. 36). (It was positive.)

- The overview of “the value of the DQP” (p. 10) includes students, faculty members, and “the public.” It should include employers as well. They have found the DQP helpful in understanding the priorities of academic programs, in developing criteria to guide hiring decisions, and in screening candidates for employment.

- The list of “guidelines for interpreting the proficiencies” could lead those seeking to make use of the DQP to find and clarify the correlations between the academic proficiencies defined there and documented employer expectations.

- The five “areas of learning” essential to any degree program (p. 12) are all germane to preparation for employment, but their importance as elements in career readiness can be spelled out more clearly. For instance, learning to collaborate with others in addressing “both conventional and unscripted problems” represents a critical “employability skill” that employers have repeatedly emphasized as a priority (p. 12). (See www.aacu.org/research)

- Similarly, the proficiencies themselves, organized within these areas in terms of the associate, bachelor’s, and master’s degree (irrespective of discipline), might include more explicit awareness of employment readiness. Three examples follow.

At the associate degree level, proficiencies expressing Specialized Knowledge might refer to appropriate employer expectations as well as to “the field of study” (p. 14). The second bullet in the list of three might be revised as follows: “Applies tools, techniques, and methods common to the field of study and to related opportunities for employment to selected questions or problems.

At the bachelor’s degree level, proficiencies expressing Intellectual Skills might include the capability of assessing not only problems “within the chosen field of study and at least one other field” but ones typically presented by careers that the student may be considering.

At the master’s degree level, proficiency in Civic and Global Learning may be demonstrated by the development of a proposal “addressing a global challenge in the field of study” (p. 19). Perhaps as an alternative students might choose to “address a challenge presented by a case study drawn from the student’s career objectives.”

As these few examples may suggest, the proficiencies defined by the DQP can easily accommodate more explicit attention to preparedness for employment. As all of the “areas of learning” invite such attention, there would appear to be no need for an additional category. But given the nay-sayers, there may be a need to reassert the unique value of the degree as opposed to credentials earned through short-term, highly concentrated programs. As Carol Geary Schneider has written, “The next edition [of the DQP] can show even more plainly why and how the combination of broad and specialized learning, consistently connected to career as well as civic applications, builds a 360-degree mindset that no short-term training program can match.”

In sum, good degree programs lead to good jobs. The DQP should say that—clearly.

All quotations are from DQP, 2014.

Blog No. 2 (July 2021)

WITH DEMOCRACY UNDER SIEGE, CIVIC KNOW-HOW BECOMES CRUCIAL

Carol Geary Schneider

President Emerita, AAC&U, Consultant, Lumina Foundation and Senior Advisor for Civic Learning and Democracy Engagement, College Promise

The ultimate test of a high-quality education is whether graduates can apply their learning productively in the wider world. With needed connections between learning and life in view, the 2014 Degree Qualifications Profile gives “Applied Learning” headline status in its matrix (pp. 22-23) depicting the core components of a quality college degree.

The DQP framework braids together broad learning, specialized learning, and intellectual skills, at all levels, from the associate degree to the bachelor’s and the master’s degrees. The key to that braiding is the students’ integrative application of learning to complex problems where the right answer is unknown. While these integrative applications may entail research projects, the 2014 DQP places recurring emphasis on putting students in real-world or hands-on settings of different kinds. The proficiency statements further prompt reflection on what students have learned from their experiences in community-based contexts.

The DQP emphasis on applied learning creates direct connections between students’ studies and their career hopes and/or experiences. And, in a previous blog, my colleague and co-author Paul Gaston did a fine job of showing how the next edition of the DQP can crystallize even further the intended connections between DQP learning and employment.

This essay, by contrast, addresses the other context for Applied Learning in the DQP, which is students’ preparation for democracy, and specifically for active participation in a democracy that is deeply divided at home, and whose actions and example reverberate—for better or worse—across the globe.

The current DQP establishes Civic and Global Learning as a necessary part of a quality degree. This is a huge strength. With democracy under siege in the U.S and facing the rise of authoritarianism around the world, we all need to reaffirm – and emphatically renew—higher education’s long-espoused role in building democracy knowledge, know-how, and commitment.

These strengths notwithstanding, the 2014 DQP is less transparent than it could be in highlighting that Civic and Global Learning also entail Applied Learning. Indeed, the whole point of broad Civic and Global learning is to prepare students to enact their roles in creating solutions to important public questions. Civic participation in a divided and inequitable democracy requires much more than voting (even though voting is indispensable). Students need strong preparation and guided practice in applying their knowledge and skills to complex public issues.

Creating that “more perfect union” further requires civic know-how – and know-how emerges, in part, from direct participation in change efforts with students themselves choosing the topics and contexts for their civic-minded efforts. The current Civic and Global Learning proficiencies do include applied learning. But that emphasis could and should be strengthened.

The revised DQP also needs to be more forthright on issues of equity and the closely related democratic principle of equality. It is commonplace now for leaders and citizens alike to say that we must solve democracy’s deep and inequitable divides. But to do so, we will need to tackle the many systemic issues we now face on many fronts: education, opportunity, food security, housing, health, digital access, social trust, racial/ethnic divisions, the environment, climate change, and more. Many of those issues are global as well as local; all of them bear directly on the quality and even the sustainability of democracy’s future. A revised DQP should be more specific in including issues like equity and disparity in its description of public problems that college students should examine.

Moreover, if democracy is to survive, Americans need to examine, not just its myriad problems, but the principles themselves. All Americans learn about the primacy of “equality” as a core democratic principle. We pledge allegiance to the principles of “liberty” and “justice.” But the meaning and application of those principles is far from self-evident, as generations of bitter contestation make clear. Students need to examine those debates and reach their own reasoned understandings of the rights and opportunities that a just democracy should bestow. They need to spend time considering democracy’s global future, in the US and the world. And they need to do so in a way that strengthens their readiness to constructively engage perspectives and experiences very different from their own.

With the above as preface, here are three suggestions to the review panels for strengthening the Civic and Global Learning component of the DQP.

Headline the importance of “Applied Learning” in Civic and Global Learning. Specifically, consider amending the title to Civic and Applied Learning, US and Global. Or to Civic Issues and Problem-solving, US and Global. Or Civic and Global Learning and Action. The idea is to give “applied learning” for the public square equal standing with applied learning for career success. Making this change would signal DQP recognition that, if democracy is to succeed, citizens must be well-prepared to combine knowledge with concerted and collaborative action.

Include “Equity,” “Inclusion” and “Social Trust” in the listing of public problems that students will explore—conceptually and through concerted action—through their associate, bachelor’s and master’s level studies. Across US education, there already is a strong drumbeat for improving equity. But too often, the intended actors are faculty, staff, administrators, and policymakers. If we want to build broad public understanding that equity solutions are needed, college study provides an optimal way to build the requisite knowledge, creative skills, and hands-on experience with real-world inequity challenges.

Make Democracy Itself a Subject of Study. Democracy is mentioned here and there in the 2014 DQP. It should be foregrounded in the revised edition. With democracy facing existential threats in the US and abroad, college study should ask students to examine democratic principles, contestations, and alternative futures. This can be done both by strengthening the democracy and equity themes in the (re-titled) Civic and Global proficiencies and also by adding “democracy” explicitly to the list of subjects that students will explore in their Broad and Integrative learning, aka, their general education studies. General education has been defended in US higher education for over a century as needed preparation for informed and participatory democratic citizenship. A revised DQP can illuminate and animate those connections, both for graduates and for a society sorely in need of new democracy commitment and capacity.

It goes without saying, of course, that strengthening the emphasis on democracy, equity, and applied civic learning in the DQP is a very small part of the solution to rebuilding our fractured and faltering democracy. So let me add that what I would most like to see is a coast-to-coast engagement with the question of how every higher education institution and system or consortia can help build new commitment, new capacity, and new civic know-how in its own context to create a more just and inclusive future.

The DQP can point the way. But it will take a movement to translate equity and inclusion aspirations into examined choices and productive action. The time to begin is now.

Blog No. 3 (August 2021)

THE DQP AND ONLINE/ASYNCHRONOUS INSTRUCTION

Peter T. Ewell

NCHEMS and NILOA

Largely driven by COVID-19, the past year has seen an unprecedented surge of online instructional delivery. This shift was precipitous, unavoidable, and unplanned with mostly unknown consequences for teaching and learning. But it raises the interesting question of how explicit statements of what students know and can do like the Lumina Degree Qualifications Profile (DQP) might make online learning better in terms of student learning outcomes. Going further, it prompts us to consider how a new version of the DQP might be deliberately constructed to facilitate this.

During this period, I interviewed faculty at multiple institutions to explore what worked and what did not in this abrupt shift to online instruction. One clear conclusion was that being ruthlessly intentional and, more particularly, focusing the design of class activities and assignments on well-defined student learning outcomes was an important success factor. The outcomes, of course, were particular to the faculty members in question and were not aligned across courses. But using a framework like the DQP would enable disparate teaching and learning encounters to be productively linked with one another to yield a more complete picture of a degree program or a sequence of courses.

More radically, the abilities embodied by the DQP might be used to construct a fully competency-based instructional approach that would be more than an online analog to face-to-face teaching and learning. Under this approach, students would master (or will have previously learned through work or prior instruction) a defined set of DQP-anchored competencies designed to constitute a given degree or program. “General education” competencies can be represented directly in the language of the DQP. Competencies associated with specific disciplines or professional fields of study could be constructed within the DQP framework of “Specialized Knowledge” using discipline-specific language drawn from the field itself. Both could then be used to design assessments and/or assignments that embody this set of competencies to be administered to students at designated points in the curriculum. This approach could certainly be actualized in a synchronous manner using traditional time-based parameters like quarters or semesters. But it could equally effectively be implemented asynchronously where students proceed at their own pace and advance as each component set of competencies is encountered and mastered.

There are several “competency-based” institutions of higher education that partially meet this ideal, though none of them do so fully. They include the College for America at Southern New Hampshire University, Capella University, and Excelsior College, among others. Each degree program at these institutions is defined by a specific set of competencies which are used to direct construction of assessments and assignments that successively certify student mastery. These assessments and assignments can be of many kinds including psychometrically sound examinations using both forced choice and open-ended responses and performance assessments in which students engage in an extended multi-faceted task in a real-world setting, with responses rated by graders using specially constructed rubrics. Students typically encounter these assessments and assignments at their own pace and prepare for them using customized study guides. At these institutions, of course, the competencies that define programs of study are unique to and defined by the institution. But there is no reason why DQP abilities could not be used to set a guiding framework for the key components of the degree and for competency-based assignments.

The main quality challenge at these institutions is serious but has nothing to do with their competency-based design. This is the fact that all of them allow students to transfer in very large numbers of credits to count toward their degrees. In a prototype DQP-based institution, this could be remediated by ensuring that students are appropriately assessed for expected learning outcomes at point of transfer.

How might the next version of the DQP be drafted to facilitate its use in competency-based instruction? Here are some suggestions:

- The next update of the DQP should be preceded by a careful and critical look at the language used to frame the competencies to ensure that it provides maximum practical guidance for constructing assessments and assignments. Guidelines for writing competency expectations were provided by the late Clifford Adelman, one of the DQP’s original authors, in a perceptive document entitled To Imagine an Verb. My NILOA Occasional Paper #16, The Lumina Degree Qualifications Profile: Implications for Assessment, also provides useful instructions for creating appropriate assignments linked to DQP competencies.

- The substantive content of the DQP should remain largely unaltered, except the workplace and civic revisions suggested by my colleagues Paul Gaston and Carol Geary Schneider in the two previous Blogs. But they should be rendered as concrete and practical as possible using real world examples wherever possible (see NILOA Assignment Library).

- The roll-out of the next iteration of the DQP should be billed as a revision of an already sound product rather than as a new document. While novelty can be a virtue, still more will be gained by positioning the document as a steadily improving edifice based on a proven body of experience.

Since the publication of its latest iteration some four years ago, the DQP has already proved its worth in describing and aligning educationally purposeful collegiate instruction. But the DQP’s content and structure can allow us to entirely remake our approach to learning by re-constituting it on a competency basis. Let’s make it happen!

AN AFTERWORD

If this were a more nearly perfect world, a fourth blog concerning revision of the Degree Qualifications Profile would appear next month. It would be incisive, informed, analytical, and highly constructive. It might also be bracingly argumentative. Above all, it would offer magisterial guidance for the revision process. It would be written by Clifford Adelman (1942-2018).

In 2010, each of the four principal DQP authors brought to the task of planning and writing a distinctive mix of expertise and experience. But Cliff brought the full package! He was a widely respected analyst, a gifted writer, a stimulating public speaker. Drawing on his extensive experience with learning data collected by the US Department of Education, he had become an influential spokesperson for the Institute for Higher Education Policy and a vigorous proponent of competency-based frameworks for learning. He embraced the creation of the “Beta” DQP in 2010 and participated fully in its revision prior to the publication of the “first edition” in 2014. He would be the first to argue that the DQP must be regularly reviewed and revised if it is to remain influential—and that it must reflect the fresh perspectives of a new generation. We wish that his voice might have been part of the discussion. But in a larger sense, given the depth and range of his contribution to the DQP and to US higher education, we believe that it is.

–Paul Gaston, Peter Ewell, Carol Geary Schneider

Blog No. 4 (February 2022)

THE DQP, TRANSFERENCE OF KNOWLEDGE, AND THE IMPORTANCE OF REFLECTION AMIDST THE PANDEMIC

Marilee Bresciani Ludvik, Ph.D.

Professor and Chair, Educational Leadership and Policy Studies

The University of Texas Arlington

The DQP has been responsive to ongoing conversations keen on clarifying learning and development expectations at various levels of learning. This conversation and corresponding updates to the DQP are taking place alongside growing understanding of how learners learn and how we know there is learning (NAS, 2018). As such, the DQP provides a framework to support those educational organizations invested in discovering how their students are “expected to perform at progressively more challenging levels.” While the DQP states it is not intended to be comprehensive, because no profile can be, it emphasizes the importance of providing illustrative expected competencies at various levels of education to assure quality and accountability as well as support conversations about the transference of knowledge from one context to another. This conversation is especially important as institutional leaders attempt to address the knowledge acquisition harm concerns related to the pandemic (DoE, 2022; Duckworth et al, 2021) as well as repair the significant uptick in students’ anxiety and stress and significant decline in students’ mental health and well-being exacerbated by the pandemic (Camacho-Zuniga, et al, 2021; Baloran, 2020; Duckworth et al, 2021). As already known, students’ levels of stress, anxiety, mental health and well-being significantly impacts students’ ability to reflect, apply learning, as well as acquire any learning they are expected to apply (Bresciani Ludvik, 2016). This simple blog shares a few questions for users of the DQP to keep in mind as they consider transference of knowledge and the importance of reflection amidst the pandemic.

Continually emerging social, emotional, and cognitive neuroscience (NAS, 2018) reminds us that the ability to apply learning, integrate learning, and or collaborate in the learning of knowledge and application of that knowledge to any process requires an integration of crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence. According to Zelazo, Blair, and Willoughby (2016),

Crystallized intelligence represents facts and knowledge that we can easily identify. We often use tests or some types of questionnaires that determine right or wrong responses when identifying whether this kind of learning is present. Fluid intelligence or executive functions are the learning and development that may appear different based on the context and culture in which they are assessed. In other words, this type of learning and development is not as easily identifiable.

To illustrate this in another way, the manner in which we teach and assess specialized/industry knowledge is often static; meaning we teach it and assess it one course/situation at a time. Knowledge conveyance is often scaffolded, as are the assessments of the subject areas that build upon themselves. For example, when we teach research methodology to students, we can teach them and then test them on the meaning of terms, what components must be included in the scientific method, etc. We can easily grade the tests and see whether there are answers in alignment with what was taught. But when we ask students to begin to apply this “knowledge” to a real-life setting, we begin to integrate experiential pedagogy and reflective practice. We don’t expect the student to be able to apply all of that crystallized knowledge without a framework that gives them and the instructors an opportunity to debrief, reflect, dialogue, critique, and try again, particularly when students’ attention on learning may be disrupted by other environmental experiences or dysregulated emotions.

The way in which we teach and assess the integration or application of knowledge/learning is often context- and culturally-specific. Thus, it can become rather elusive to identify in other contexts and cultures as the transference of that learning may not be readily evident. It may not be readily evident because the learner isn’t able to adopt and adapt what was learned in a different context and/or culture than the one that was assessed. Or it may be that the application of that learning doesn’t align with the manner in which it is being assessed. In other words, the context and culture of the applied learning or the collaborative learning are not represented in the assessment tools. Let’s take an example, the DQP Analytic Inquiry competency for the bachelor’s degree—“Differentiates and evaluates theories and approaches to selected complex problems within a field of study/industry/profession and at least one other field.” How might one go about assessing? Here are some potential steps:

- A student must first be tested on crystallized intelligence with regard to theories and approaches that exist. We want to first ascertain whether the student has this knowledge in their knowledge toolbox.

- Next, there are a number of skills in their skill toolbox that needed to be cultivated in order to “differentiate and evaluate.” For example, we would need to make sure they have been taught and assessed on what comparison means and how to look for patterns, spotting differences, and doing so quickly.

- Then we would have had to ensure that the student understands what evaluation means through answering the following questions:

- Are they able to differentiate between what is working and what is not working;

- More importantly, are they acknowledging that these skill sets are transferrable?

- How confident are they in their ability to discern which tools they will need out of their knowledge toolbox (crystallized intelligence) and their skills toolbox (fluid intelligence) as they are now asked to apply these tools to a complex problem in their own discipline and now in another discipline for which they may have fewer tools in their knowledge toolbox to draw on?

- Intentionally addressing the pandemic impact, how well are students able to skillfully regulate (as opposed to avoid, deny or suppress) their emotions to optimize their attention and engagement in the reflection of their learning within a specific context.

In this example, we want to make sure students have had the opportunity to cultivate and are aware of a vast array of tools in their skills toolbox that they can draw on, such as attention regulation, emotion regulation, reflective learning and metacognition.

The importance of cultivating reflective learning as well as other malleable neurocognitive skill sets such as attention regulation, emotion regulation, self-regulation, sense of belonging, prosocial values, grit, and many others comes into play for the learner, the teachers, and the assessors (NAS, 2017). It is important to note that there is no arrival when engaging in reflective learning. Malleable skill sets necessary for learning also have no arrival point. The ability to pay attention on demand, the ability to name what is being noticed, whether it is awareness of having memorized a fact or naming where that fact should be implemented in a problem-solving scenario or naming the emotions that are arising from not comprehending all the cultural nuances of this new setting have no ending points. Determinations of applied learning and neurocognitive skill competency attainment are context- and culturally-specific.

Metacognition is the practice of naming the reasoning behind known understanding by identifying the planning, control and evaluation behind the understanding (Maryati et al., 2020). Further, metacognition is built upon reflective practices. Students’ capability to monitor their progress towards their desired competencies, name what they know and do not know, as well as what they can and cannot do, and then adjusting their learned learning strategies are measure of one’s metacognitive awareness (Zafarmand et al., 2014).

There are many things we do and do not know about how learners learn. As important, if not more importantly, there are many things we do and do not know about how well learners know they are learning or that they know what they have and have not learned. It is extremely important for learners to be able to articulate how empowered they feel to seek support when they are aware they are not able to apply what they know in a different context and/or culture. And this then invites in the opportunity for the educator to cultivate other malleable fluid intelligence skills such as environmental mastery, purpose in life, autonomy, self-compassion and other skill sets that build persistence, well-being, and positive goal-oriented behaviors. The ability to identify application of crystallized and fluid intelligence learning is context and culturally specific.

What does this mean for the DQP? It could mean that in addition to the very well-articulated and important outcomes for each degree level, there also exists an expectation for learner reflection of two primary things (there can be more, this is just an example).

- In what contexts and cultures and using what strategies does the learner find it easy to apply said knowledge or said skill?

- What does it look like for the learner when they are not able to apply the knowledge or skill in a particular context or culture? What are they noticing worked well and didn’t work well? What strategies worked well and which strategies failed?

- What does it feel like for the learner when they are not able to apply the knowledge or skill in a particular context or culture? What are they noticing worked well and didn’t work well to regulate (as opposed to avoid, deny, or suppress) those feelings so they become more empowered to act? What strategies worked well and which strategies failed?

- When did the awareness of what working or not working well arise? In what ways did the student respond to that awareness? What does the student feel empowered to do in order to succeed at trying again? What support/help/resources do they need to be successful as they try again?

- What action did the student next take as a result?

Building this into the DQP as a learning outcome or competency may mean simply rephrasing it as “the learner is able to a) identify which contexts and cultures they are able to apply these competencies in; and b) explain what they found difficult to apply in a specific context and/or culture and illustrate the reflective practices they used to meet that challenge,” etc. Assessing the response to transference of knowledge and applied reflective practice so that fluid intelligence continues to build will likely reside in the use of multiple methods and multimodal methods.

References

Baloran, E. T. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, anxiety, and coping strategies of students during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(8), 635-642.

Bresciani Ludvik, M. J. (Ed.). (2016). The neuroscience of learning and development: Enhancing creativity, compassion, critical thinking, and peace in higher education. VA: Stylus.

Camacho-Zuñiga, C., Pego, L., Escamilla, J., & Hosseini, S. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ feelings at high school, undergraduate, and postgraduate levels. Heliyon, 7(3), e06465.

Department of Education (2022). Education in a pandemic: The disparate impacts of COVID-19 on America’s students. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/20210608-impacts-of-covid19.pdf

Duckworth, A. L., Kautz, T., Defnet, A., Satlof-Bedrick, E., Talamas, S., Lira, B., & Steinberg, L. (2021). Students attending school remotely suffer socially, emotionally, and academically. Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211031551

Maryati, S. S., Purwanti, I., & Mubarika, M. P. (2020). The effect of brain based learning on improving students critical thinking ability and self regulated. IJIS Edu: Indonesian Journal of Integrated Science Education, 2(2), 162-171.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Supporting students’ college success: The role of assessment of intrapersonal and interpersonal competencies. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24697.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/24783

Zafarmand, A., Ghanizadeh, A., & Akbari, O. (2014). A structural equation modeling of EFL learners’ goal orientation, metacognitive awareness, and self-efficacy. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 5(6), 112-124.

Zelazo, P. D., Blair, C. B., & Willoughby, M. T. (2016). Executive function: Implications for education. NCER 2017-2000. National Center for Education Research.

Official DQP and Tuning Archive!

NILOA now serves as the official archive for all materials related to DQP and/or Tuning efforts that were undertaken in partnership with the Lumina Foundation beginning in 2011. If you are interested in obtaining or reviewing any DQP or Tuning-related information, please contact niloa@education.illinois.edu.